Every student has sat in a classroom, wondering when they would ever use the things that they are learning in the real world, or at all. In no classroom has this happened more than in a math classroom, and it’s not really that surprising why: we are taught wrong.

Math taught without mathematical thinking is akin to teaching literature by only memorizing the alphabet. Over time, students may understand the syntax and even begin to put some words together, but there is a broader and far more meaningful message to appreciate. To many, math is a mystery because they have only ever been taught the “alphabet” of math. An unintuitive and confining ten-or-so years of math curriculum has given it the reputation it earns with many students: boring. Even if you’re one of those students, there is one thing you absolutely cannot do, and that is to believe you aren’t good at math. Just because of the disservice the education system (no hate to Minnetonka, it’s an everywhere thing) has done you, doesn’t mean that the creative mathematical spark is gone.

“If you are exposed to [mathematics] in a way that interests you … you find that you actually [like it].” said Professor Richard McGehee, a professor of applied mathematics and dynamical systems at the University of Minnesota. Although it’s a simple idea, it’s true. One good teacher or even a change in your life can completely shift a person’s perspective on anything, especially math. This happened for 2 graduate students supervised by Professor McGehee: after getting an undergraduate degree in biology, and then spending two years in a lab, they shifted to working towards a PhD in mathematics. Stereotypes and preconceived notions can also act as a barrier to mathematics. As is the unequal and unfair reality of many fields, men occupy more space in the mathematical landscape: across 5 Ivy League schools, only an average of 16.4% of the people earning a PhD in math were women (MIT). Professor McGehee says that in his experience of supervising PhD students, “two [of his] most creative thinkers were women.

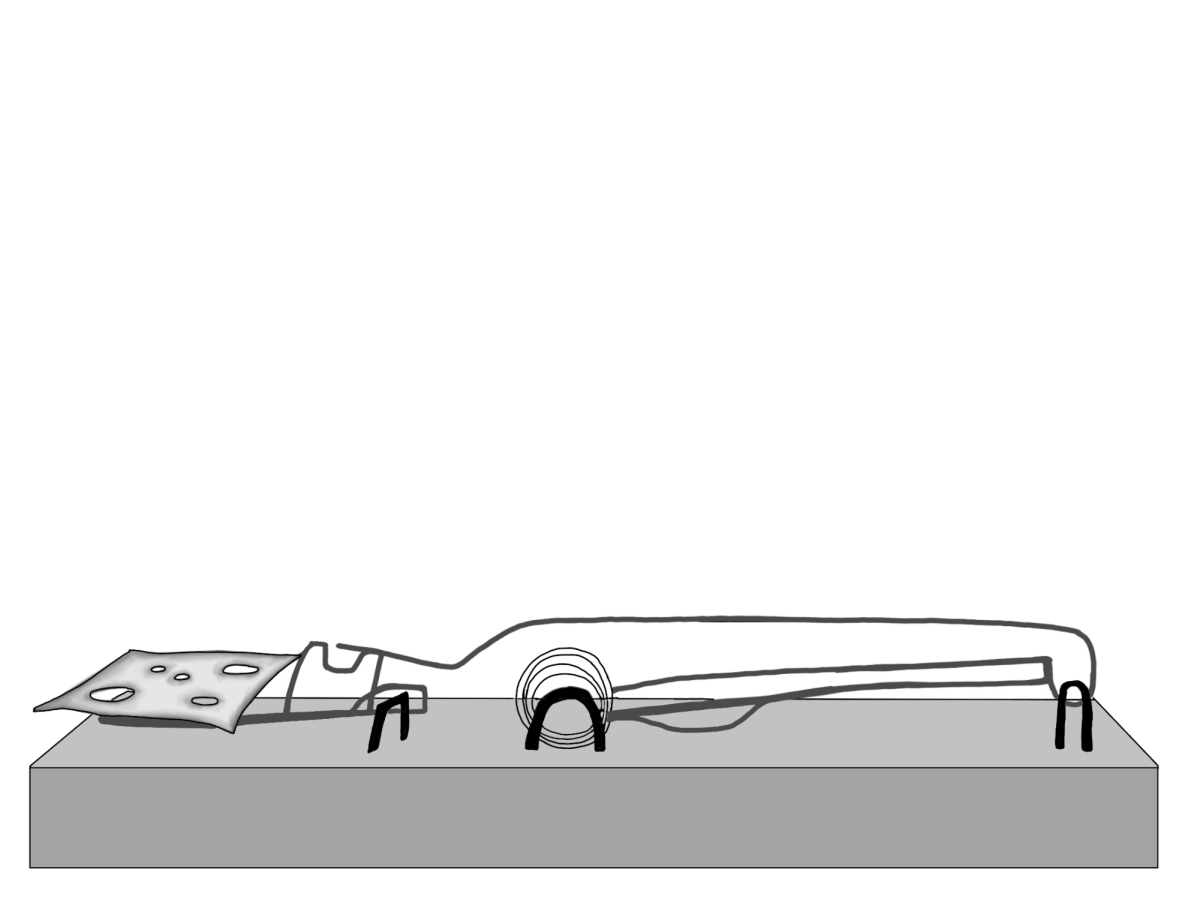

The magic of math is that it is a discipline of abstraction. It takes real-world scenarios, everything in the world around us, and allows us to put it on paper, manipulate it, and explore it. The basic number system is an abstraction: instead of drawing three coconuts everytime we want to reference three of something, we write the symbol 3. When there is a process – say, a car moving, – it can be abstracted to an f(x) = y, where x is what goes in and y is what comes out. When only the abstraction is taught, without any motivating problem, math becomes boring. We are taught the quadratic formula, trigonometric identities and rules, prime factorization, integrals, and derivatives, before we are given any context or motivation. By this pedagogy, math quickly becomes nothing more than rearranging symbols and rote memorization of formulas that students wouldn’t be able to derive themselves. Instead of being taught from the ground up – knowing why it’s b squared, and why it’s all over 2a – we are taught the other way around, and by the time students are taught the foundational and intuitive parts of mathematics, it’s too late. We have already abandoned the idea of finding joy in the problem solving process or the childlike excitement of coming up with a clever solution, because we have never gotten anything close to a satisfactory answer to the question, “what’s the point?”