Although the most popular U.S. sport is football, not many people are aware of the rich history that embodies modern-day fencing. This niche sport can be equally as demanding as soccer or football, relying heavily on complex technical actions. It’s unsurprising that fencing has a deep history. Even the handshake at a tournament is reminiscent of Ancient Greek fencers from thousands of years ago. The handshake acknowledged that although both fencers were fighting against each other, they respected each other’s sacrifices to strengthen their mental and physical skills.

The sport truly developed its main objective in the mid-1700s, when French fencer Domenico Angel revolutionized the sport in a way that still applies to fencing today. Due to Angel’s efforts, modern fencing gradually diverged from its bloody origins to focus on precision rather than brutality. Today’s Olympic-style combat fencing has many safety precautions. The goal isn’t brutal hits, but for your blade to make contact with the target area of the opponent; making one “touch” scores a point. To track points, electric technology and gear is used.

Olympic events are categorized by the three swords: Foil, epee, and saber. Foil is the lightest sword, and in order to score a point, you must use the sword to stab your opponent’s torso. Epee is also a stabbing sword, which means you can only score using the tip of the weapon. Its target area is the opponent’s entire body. Saber is a slashing sword, meaning that a point can be scored with the sides of the blade, as long as it hits the waist-up target area. Foil and saber follow right of way, a complicated set of rules that determine which fencer receives a point when they both hit simultaneously.

In all regular individual tournaments, fencers’ skill levels are first assessed with a pool round. After fencers get a ranking based on performance in previous events, they compete in small mixed-skill groups, which helps officials rerank them. With the final rankings, officials prepare a tableaux for the 15-touch elimination round. The top fencers compete with each other last, which ensures that the best fencer doesn’t eliminate the second best fencer in the first round.

Last year, fencing nationals took place during the summer in Columbus, Ohio, which broke the record for the biggest USA national ever. Key Kronzer, ‘27, is a fencer who competed in nationals last year through the Youth Enrichment League, which is Minnesota’s top fencing club. Next year, summer nationals will take place in Milwaukee.

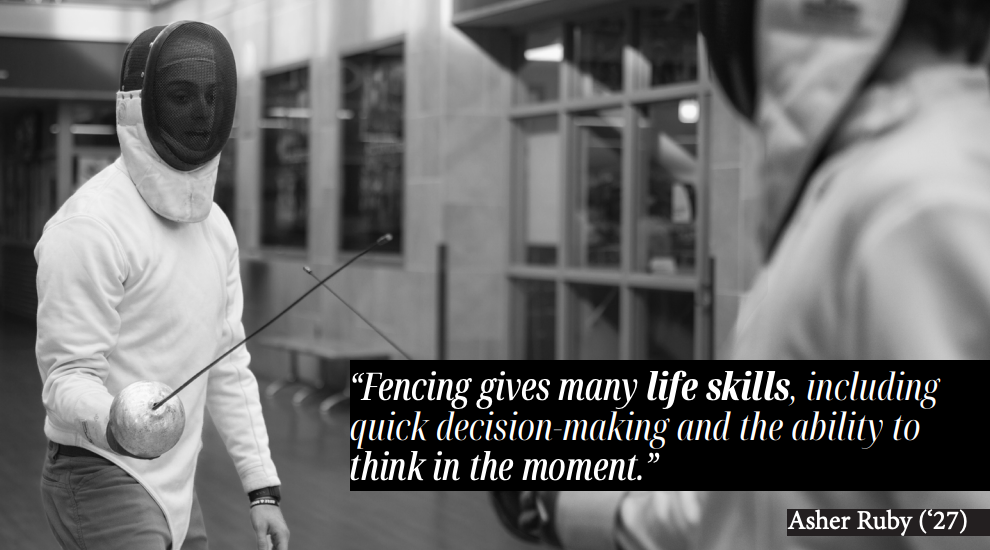

Kronzer’s fellow teammate Asher Ruby, ‘27, who is competing in Milwaukee nationals, says that “Fencing gives many life skills, including quick decision-making and the ability to think in the moment.” The philosophical principles that the Greeks devised still ring true to the sport, which is another reason why it’s worth learning about. After all, fencing has deeply historic origins that have far preserved longer than most of the other sports at MHS.