100 grams was all it took for Indian wrestler Vinesh Phogat to be disqualified from the women’s 50kg wrestling final at the Paris Olympics. Despite making the weigh-in on the first day of the final, Phogat was required to drink water to prevent dehydration, causing her to gain more weight than expected. In the months following Phogat’s eventual retirement, countless doctors and sports analysts have raised discussions on whether her coaches’ questionable decisions reflected the toxic practices of wrestling.

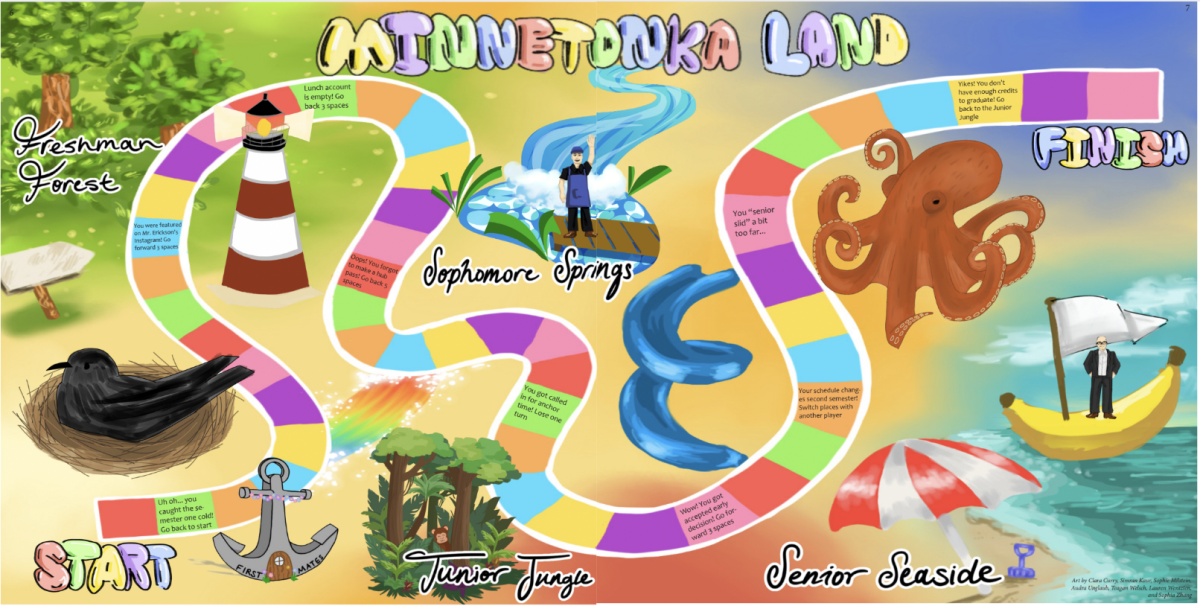

The media attention surrounding Phogat’s disqualification has caused a resurgence in concerns of weight-cutting not only for Olympic levels, but for high school level wrestling as well. To reassure parents and teachers about the safety of MHS wrestlers, it’s understandable why “ensur[ing] the safety and well-being of our wrestlers, coaches, and fans” is the number one goal on Tonka Wrestling’s website for their 2024-2025 season. With MHS’s long-anticipated kickoff tournament on November 30th right around the corner, it’s helpful to learn about the process of weight cutting and how it has changed in recent times.

When athletes in weight-class sports want to qualify for a lower weight category, they “cut weight” prior to a match to fight a weaker opponent. To deal with weight categories filled with athletes at their lowest fat percentage, wrestlers cut weight through a variety of methods, each with their own effects.

One way is by manipulating the body’s water and energy stores through diet and exercise—while dangerous, it isn’t as fatal as excessive dehydration and sweating. These methods can lead to impaired function of the blood, kidneys, and cardiac system. Luckily, more extreme weight cutting attempts such as vomiting, diuretic use, and laxatives have been rarer since the NCAA altered its regulations in 1998 after the death of 3 athletes.

Because regulations for high schoolers are often less enforced depending on school and area, weight cutting has historically impacted the psyche of young wrestlers, leading to eating disorders. However, regulations have greatly improved since the last generation of wrestlers. As of 2022, the NFHS set minimum body fat percentages at 7% for males and 12% for females to discourage excessive weight loss.

While new rules are being implemented slowly, high school wrestling is slowly phasing out of its toxic past, and some former wrestlers say that the issue has been dramaticized by the media. However, health experts emphasize how crucial natural growth is for young wrestlers.

Weight-cutting has come a long way throughout the history of wrestling. It’s important to realize that wrestler safety is prioritized at MHS. “Nobody really cuts anymore because it’s just not really healthy,” says Brayden Morvig, ‘24. “It’s only if you’re like D1 and you are really interested in wrestling, that’s when you cut weight and stuff,” Morvig’s teammate, ‘27, added. With wrestling season approaching, more gratitude is owed to coaches who ensured that the pressure of toxic weight cutting would not be passed onto the next generation of wrestlers.