Political Correctness in Schools and Colleges

November 15, 2016

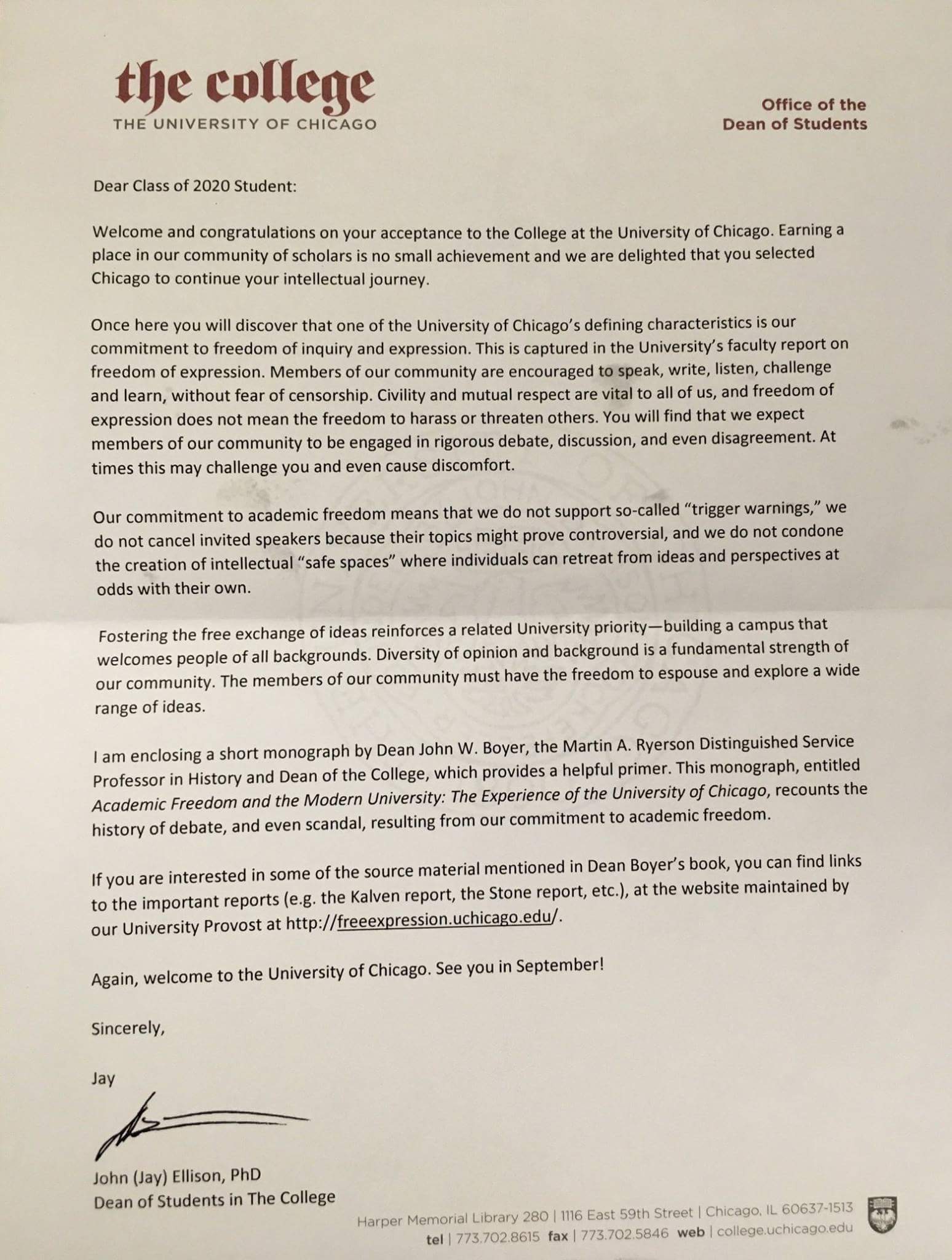

“University of Chicago Strikes Back Against Campus Political Correctness,” proclaimed a New York Times headline on August 26, two days after a letter from the Dean of Students was received by incoming university freshmen that seemingly condemned so-called safe spaces and trigger warnings. This letter comes after three speakers on campus in the past year have been shut down by protesters.

Our commitment to academic freedom means that we do not support so-called “trigger warnings,” we do not cancel invited speakers because their topic might prove controversial, and we do not condone the creation of intellectual “safe spaces” where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.

–John Ellison, Dean of Students

Minnetonka Breezes interviewed Riley Sester, an incoming UChicago freshman and recent graduate of Minnetonka High School, to get his thoughts on the Dean’s letter, political correctness in general, and his experience with the topic here at Minnetonka.

“My first impression was that [the letter] stood for everything the university stood for, […] free expression and free exchange of ideas, and diversity in opinion and background.” Riley also stated his support for the university’s supposed position against intellectual safe spaces.

The concept of safe space has been a source of great controversy following the August 24th letter. Sester touched on this issue in his interview, offering that there is not one “clear-cut definition of safe space.”

“To me, based on the rest of the letter and the context behind it, safe space is referring to an intellectual, physical location, where only one aspect or one side of a situation is represented, and only that one side is allowed to exist. Does that necessarily go so far as to encompass support groups and religious organizations, based on my knowledge of the student groups at the university, no. And that’s part of why this is a debate, because it’s a gray zone.”

The Office of LGBTQ Student Life runs a “Safe Space Program” at UChicago, which maintains overwhelming support from the faculty, administration, and student body. While the Dean’s letter does technically refer to intellectual safe spaces, many critics of the letter, including Student Government President Eric Holmberg, argue that the letter does little to emphasize this important distinction.

The debate surrounding trigger warnings shares many similarities with that of safe spaces; however, there is generally greater consensus on its meaning. Trigger warnings commonly refer to notices given before texts or speakers warning that the content may be traumatizing to some people. Sester believes that there is a gray zone surrounding this issue as well.

“On the one hand, do I think that a victim of rape should be forced to unknowingly read in a text a graphic depiction of a rape? No, of course not. But then, it also goes to the point where somebody who feels uncomfortable by a topic can back out and not read about it because it’s at odds with their own ideas. [That is] not something that I would personally ever support, and [I] think that you should be exposed to all ideas and different viewpoints.”

In three separate instances over the past year, student protests on campus have interrupted speakers, including Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez and Palestinian human rights activist Bassem Eid. This has brought up issues in the administration regarding potential disciplinary action for the protesters responsible. Since protesters are exercising their right to free speech, punishment seems to run counter to the University’s recent statements in the Dean’s letter. Regardless, Ellison and Holmberg share Sester’s stance that “speakers should never have to be cancelled at a university because some groups might be offended, or think of [a topic or speaker’s viewpoint] as too controversial.”

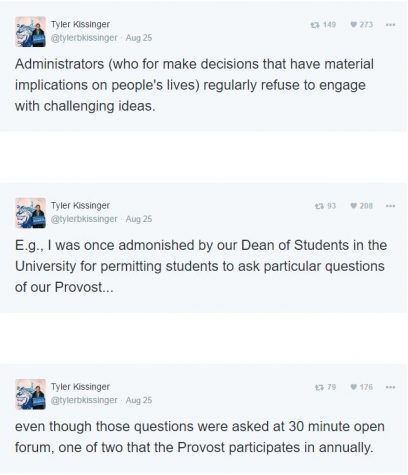

Former Student Government President Tyler Kissinger repeatedly clashed with the UChicago administration during his time on campus. He replied to the Dean’s letter through a series of tweets on August 25 which critiqued Ellison’s statement as being hypocritical.

Additionally, a group of over 170 members of the UChicago faculty have signed a Letter to the Editor of the Chicago Maroon in response to the Dean’s letter, striking a very different view of the topic.

The debate over political correctness has escalated in recent years, especially in the area of politics. People on both sides of the issue have accused the other of being extreme, and politicians often draw on these strong feelings to garner votes and rally support.

“To me, it is both a way of respecting individuals and their differences, but can also be a way of restricting ideas and prohibiting free speech,” replied Sester when asked about his opinion on the concept of political correctness. “In a lot of cases, I think that political correctness is a hindrance to free speech and freedom of expression, but that does not mean that it’s an excuse to be disrespectful or, at an extreme, commit hate crimes.”

At times, the debate about political correctness may seem far removed from life at Minnetonka High School. However, it is important to examine the manners in which this idea, and others like it, shape the community and learning environment in ways both obvious and subtle.

Sester recalled his experience in an AP Literature and Composition class discussion about the use of manipulative language by politicians.

“Somebody had found something that they interpreted as being manipulative and political, but that others did not. And we had the discussion and we talked about it, and it was that situation that, to me anyways, represented a more open and free community space to talk about something that, in another situation, might not have been discussed. It was just very much opposition of ideas, but the teacher kept going, and we discussed it.”

Sester described a similar situation in US Government and Politics where an open environment allowed for free discussion without fear of “[offending] anybody else, because everybody relishes your opinions and ideas.”

While Sester’s classroom experiences at Minnetonka were largely positive and promoted respectful and open-minded discussion among individuals with diverse beliefs, not all learning happens in the classroom. Students learn much from each other simply by conversing in a casual setting.

“I think it’s easy to discuss these kind of topics in a classroom setting, but what I would say that, in more negative lighting, is outside the classroom, people are–in my experience anyways–extremely hesitant to discuss something that might be considered controversial, be it politics, religion, anything like that. People don’t want to offend anybody, and they’re afraid to offend people, and to me that’s not a healthy way to go about living in general.”

Sester further shared his thoughts around this reluctance to engage in critical thinking regarding contentious topics.

“If you come across an idea that’s at odds with your own, discuss it. You should be able to debate it; if you can’t debate it, then abandon your ideas. You know, if your ideas can’t be defended, and they’re illogical, then [you] shouldn’t hold them, so you should absolutely be comfortable discussing your ideas with anybody. And I think that that kind of setting outside the classroom, where people are too scared or too hesitant to discuss anything they might think is controversial, that’s an extremely detrimental environment.”