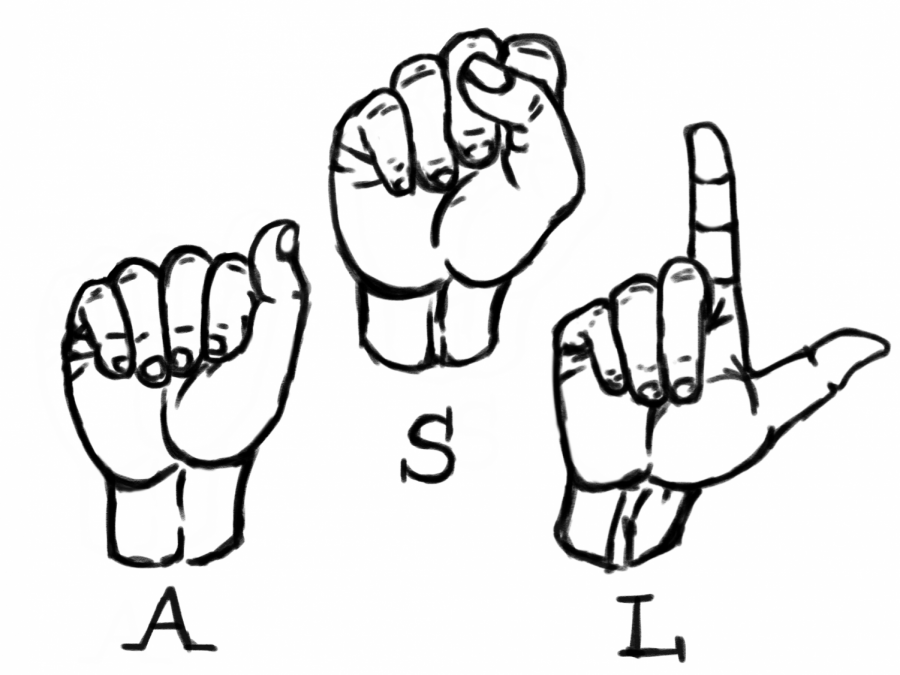

American Sign Language: Foreign Language Option or Visual English?

March 20, 2020

Most high schoolers are accustomed to the idea of fulfilling a foreign language requirement before graduating and applying to postsecondary schools. While many gravitate towards spoken languages such as Spanish or French, some students develop a passion for American Sign Language (ASL), using the hands to convey messages rather than the voice. However, several get caught up in the idea that ASL isn’t always considered a foreign language and fear it may not be recognized as one on their transcript. While ASL is recognized as a method of communication, many still believe it to be a less credible form of the English language. So, which is it?

Before American linguist William Stokoe’s extensive research of the visual language, ASL was merely regarded as a gestural imitation of speech. However, as he observed signers in action, he recognized they used not only hand gestures, but facial expressions, lip and mouth movements and body orientation to communicate. This, along with the clear use of syntax and morphology, Stokoe perceived led to the recognition of sign languages across the globe as genuine languages in the 1960s.

However, the evidence collected over half a century ago validating ASL as a language appears to now be questioned. While many post-high school programs are beginning to permit ASL to fulfill the necessary foreign language requirements, many individuals still struggle to classify ASL as a true foreign language.

One of two primary arguments against ASL being a foreign language is how it is used primarily in the United States and therefore isn’t technically foreign. While the roots of ASL are planted in America, ASL is also taught across much of the globe. Students who elect to take ASL as their language are in fact participating in education of a foreign language, only defining ‘foreign’ slightly differently than being explicitly from a different country.

“A foreign language to me… means [it is] unfamiliar and ASL is not a language that is widely known,” said Caitlyn McKirahan, ‘22, currently enrolled in ASL.

ASL proves to be foreign as students learning about the language must also learn about deaf culture associated with ASL, a foreign culture to non-native signers.

Connor Garroch, ‘22, highlighted that deaf culture is “an entirely different community, so even though [ASL] might still be ‘American,’ [native signers] have a different culture as well as traditions.”

Just as both the French and the Spanish have their own individual cultures, deaf people formulate their own culture that can only be understood to a certain extent by the hearing, thus revealing more similarities between the visual and spoken languages.

The other argument questions the validity of ASL as a foreign language as it has no written form other than English.

“The argument doesn’t hold any water because we have a visual version of books, like talking books for the blind,” says Dr. Roselyn Rosen, former dean of the College of Continuing Studies at Gallaudet University in Washington.

As books and verbal languages are able to communicate stories and illustrate different experiences through various types of diction, ASL is able to convey the same ideas, perhaps even more efficiently and in depth.

With the 3D element of ASL, stories can be told by acting them out rather than by using words, making it more lifelike for the listener to feel a part of the story.

Dr. Wilcox, a linguist at the University of New Mexico, also compares ASL to an oral culture; oral cultures pass down traditions and customs from one generation to the next without documentation.

“Most languages of the world are unwritten. You can have literature without it being written,” he said, “making it clear that ASL should not be an exception.”

To answer the initial question, ASL most certainly is a foreign language. The ‘foreign’ aspect is simply different than what the hearing community perceives it to be. This only further demonstrates the need to gain a better understanding of ASL and deaf culture before making assumptions about the language’s validity.