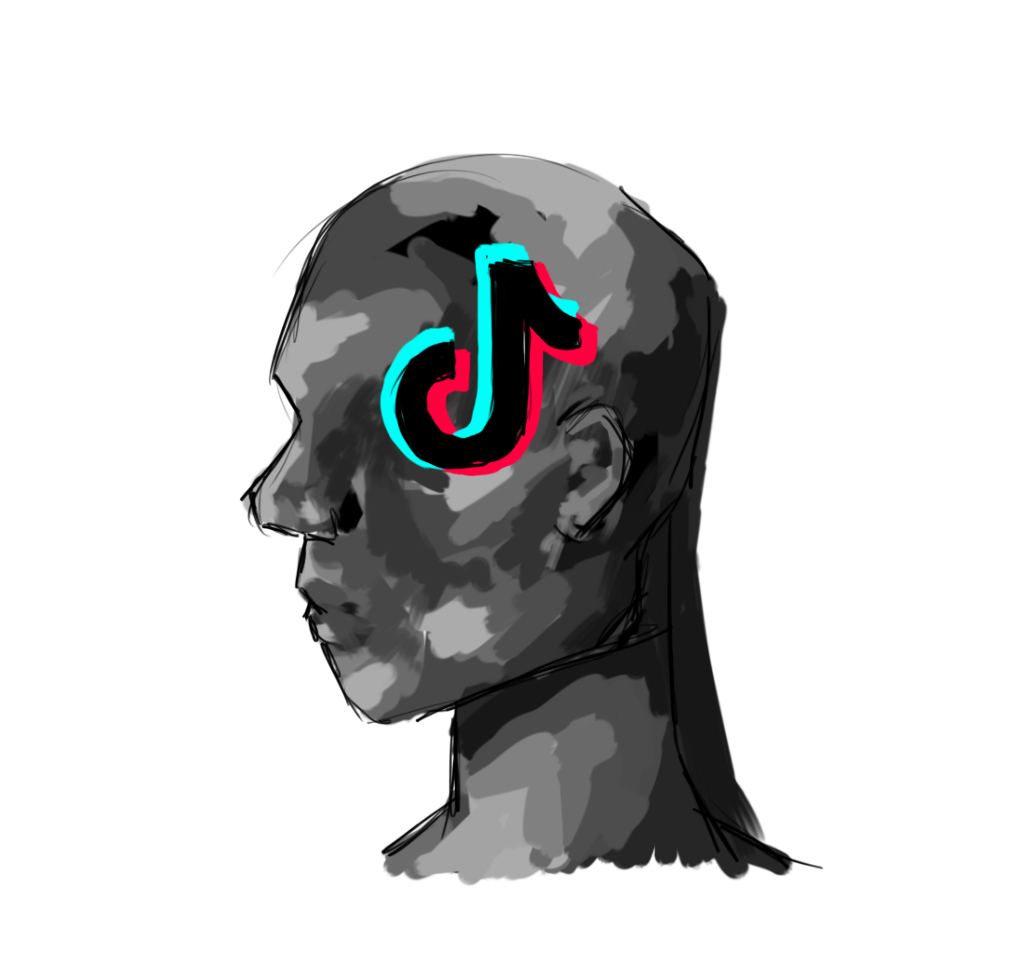

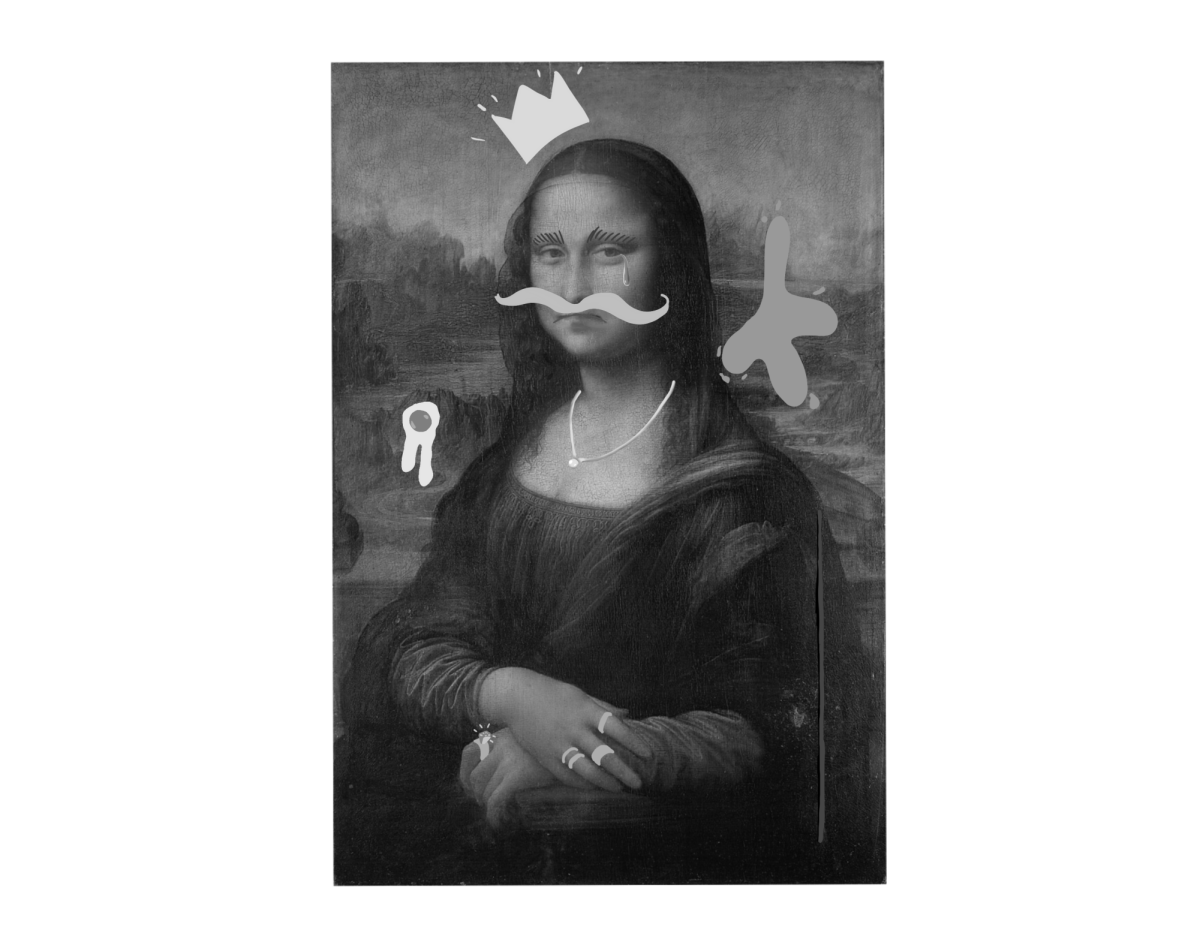

Just Stop Oil protesters are past their viral prime of being criticized for aiming soup cans at innocuous dead painters to express their environmental frustration. The organization still makes headlines, but it’s usually about their newest addition to the organization’s encyclopedic list of prison sentences. Although TikTok has grown unfazed by art demonstrations that once collectively offended the nation, these protests are far from a trendy series of isolated events. Just Stop Oil activists have not only popularized defacing art as a political protest, but have also changed what it means to deface art in the age of social media.

In fact, movements across the political spectrum have been defaulting to art when they want to make a political statement. Even hateful groups turn to art as their platform of choice. Most recently on January 18th, a Japanese-owned art exhibit in Seattle had a mural vandalized, in which the suspect blacked out the faces of Japanese Americans during WWII internment camps.

The key reason why art is such a target for political activism is deeply rooted in the evolution of art itself. Throughout history, activists and their intentions have evolved alongside the art that they protest against. In 1880, an exhibition by the Russian painter Vasily Vereshchagin was vandalized by monks of the Catholic Church due to representations of the Bible deemed too graphically realistic. As time progressed, tensions between the Russian Impressionist movement and western abstract movements swelled. However, the vandalism also reflects an emergence of increasingly nuanced political dynamics, highlighted by the political counter-reform of Alexander III and the Pochvennichestvo who opposed the westernization of Russian society.

As abstract art became popularized, protests against art highlighted the uncertainty of political dynamics. In 1997, performance artist Alexander Brener smuggled a can of green spray paint into a museum and painted a green dollar sign over Kasimir Malevich’s white-onwhite painting Suprematism, which was meant to reflect the commercialization of art. Brener viewed his action of painting the dollar sign on top of the cross as an open dialogue between Malevich and himself, stating that “Malevich wanted to change the world using art. But now he is just a commercial site.”

However, there’s something fundamentally different about how modern Just Stop Oil protests led activists’ immediate jump to art as the default form of activism: museum videos of vandalized paintings provide a global social media presence for these protesters. Even in the case of Brener’s protest just before the emergence of modern technology, his goal was to make a statement about the institutions of art. Brener’s immediate escape from the premises can reinforce how the focus was on the issue at hand, not him. When you watch Just Stop Oil protestors unashamedly throwing a can of tomato soup at Van Gogh’s most famous pieces and refusing to move in full view of museum-goers eager to gawk with their phones out, it’s clear that they are incorporating themselves as a part of the center focus.

Even if their protest relates to the subject of the art, activists are now aware that the efforts of their vandalism will be fully available online for the global audience to see. The wide variety of activist organizations that use art as a platform for attention often matches the unpredictability of social media. The appeal of art itself has been restructured from art’s message finding itself in the hearts of the public to art advertising itself as a prepackaged, desired public perception.

Although their actions may be more intentional than those of the internet era, Alexander Brener and the Catholic Church of Russia ultimately never created a massive movement through their protests. From Russian Constructivism to the Dada “anti-art” movement, the art world has made its biggest societal changes through the creation of more art. Just Stop Oil is giving in to the same social media appeals that promote consumerism and an obsessive focus on the public. It would bring a refreshing value to the digital age if a new art movement took advantage of the global audience and empowered crowds beyond surface-level shock value. Ava Hustad, ‘27, says that social media’s role in art is a “double edged sword. It glorifies art trends rather than individual creation, but it also allows for art communities to grow and thrive with their own styles and subjects.